Technological University Dublin

ARROW@TU Dublin

Dissertations Social Sciences

2019-4

Social-Emotional Intelligence (EI), graduates and the workplace – A study of a tailored approach to EI competency development for final year engineering students

Ailish Jameson

Technological University Dublin, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Communication Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation

Jameson, A. (2019). Social-Emotional Intelligence (EI), graduates and the workplace – A study of a tailored approach to EI competency development for final year engineering students. Technological University Dublin. DOI: 10.21427/GWGM-3G82

This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],

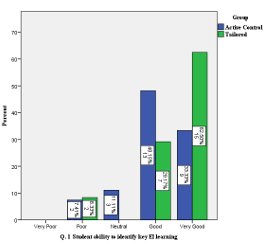

[email protected].

Social-Emotional Intelligence (EI), graduates

and the workplace – A study of a tailored

approach to EI competency development for

final year engineering students

By

Alice Jameson

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)

Awarded by: QQI

Supervised by:

Dr Aiden Carthy (Lead)

Technological University Dublin (TU Dublin) – Blanchardstown

campus

and

Dr Colm McGuinness (co)

TU Dublin – Blanchardstown campus

and

Dr Fiona McSweeney (co)

TU Dublin – Dublin City Campus Grangegorman

April 2019

Table of Contents

Declaration ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………………………

Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

List of Tables………………………………………………………………………………………………..

List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter One : Introduction and Overview ……………………………………………………

1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………

1.2 Overview of higher education ……………………………………………………………..

1.3 Aims and objectives …………………………………………………………………………..

1.4 Research questions …………………………………………………………………………….

1.5 Social-emotional (EI) competency in the workplace – importance and current levels …………………………………………………………………………………….

1.6 Tailored versus general EI coaching …………………………………………………….

1.7 EI coaching and employability …………………………………………………………….

1.8 Structure of the thesis …………………………………………………………………………

Chapter Two : Literature Review ………………………………………………………………..

2.1 Section One: Historical Evolution of EI ………………………………………………

2.1.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………

2.1.2 Emotion …………………………………………………………………………

2.1.3 Emotion and the Brain…………………………………………………………………………

2.1.4 Intelligence…………………………………………………………………………

2.1.5 EI …………………………………………………………………………

2.1.6 Model of EI …………………………………………………………………………

2.1.6.1 Trait Theory ……………………………………………………………………….

2.1.6.2 Salovey-Mayer Ability Model ………………………………………………

2.1.6.2.1 MSCEIT …………………………………………………………………………..

2.1.6.3 Goleman and Boyatzis– Emotional and Social Competence Inventory (ESCI)…………………………………………………………………

2.1.6.4 Bar-On Model of Emotional and Social (EI) Functioning ………..

2.1.6.4.1 Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i2.0) ……………………………….

2.2 Section Two: EI and Higher Education ……………………………………………….

2.2.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………

2.2.2 The bologna Declaration on the European space for higher Education …………………………………………………………………………

2.2.3 The Nation strategy for higher Education to 2030……………………………………………….

2.2.4 Marketisation of Education …………………………………………………………………………

2.2.5 EI and Graduate attributes …………………………………………………………………………

2.2.6 Graduate Attributes : University of Aberdeen ,Scotland and TU Dublin…………………………………………………………………………

2.2.6.1 University of Aberdeen, Scotland ………………………………………….

2.2.6.2 TU Dublin ………………………………………………………………………….

2.2.7 Graduate attributes and engineering students………………………………………….

2.28 The Journeymen project,Sweden and the professional Entity project, Australia ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3 Section Three: EI, graduates and the workplace …………………………………..

2.3.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.2 Employability ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.3 EI and the Workplace ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.4 Coaching ………………………………………………………………………….

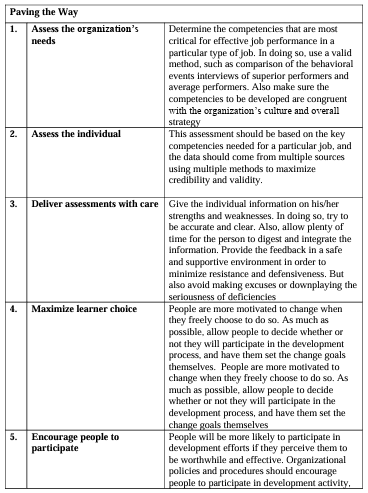

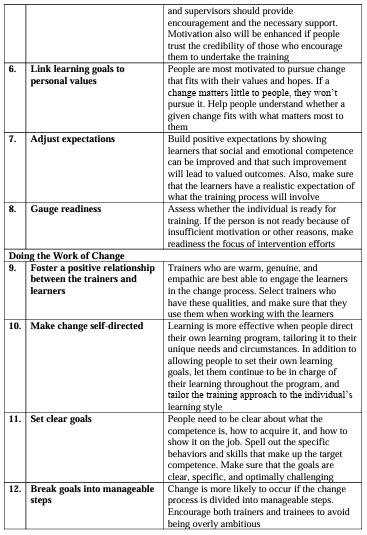

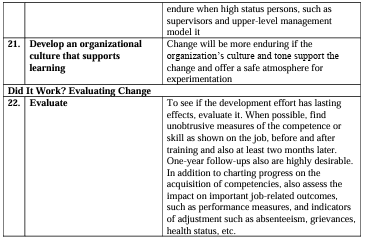

2.3.5 The Consortium for Research on EI in Organization -Guidelines for emotional competency training ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.6 EI coaching based on the Bar-On Eq-i2.0 ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.7 EI coaching in the workplace-case studies ………………………………………………………………………….

2.3.7.1 American Express Financial Advisers (AEFA) ……………………….

2.3.7.2 Fortune 400 ………………………………………………………………………..

2.3.7.3 ‘Search Inside Yourself’ (SIY) EI coaching programme ………….

2.3.7.4 conclusion ………………………………………………………………………….

Chapter Three : Method …………………………………………………………………………….

3.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………..

3.2 Theoretical Framework …………………………………………………………………..

3.3 Research Paradigm …………………………………………………………………………

3.3.1 Positivism ………………………………………………………………………….

3.3.2 Constructivist/ Interpretivism ………………………………………………………………………….

3.3.3 Critical Theory ………………………………………………………………………….

3.3.4 Pragmatism ………………………………………………………………………….

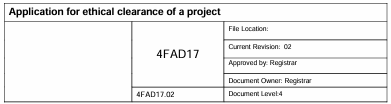

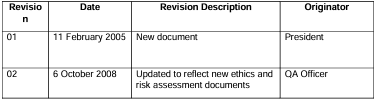

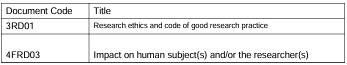

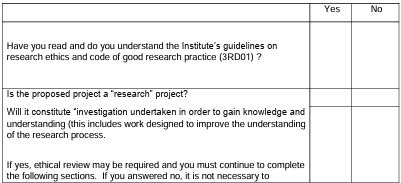

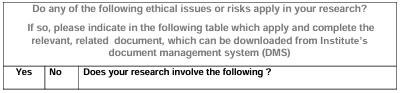

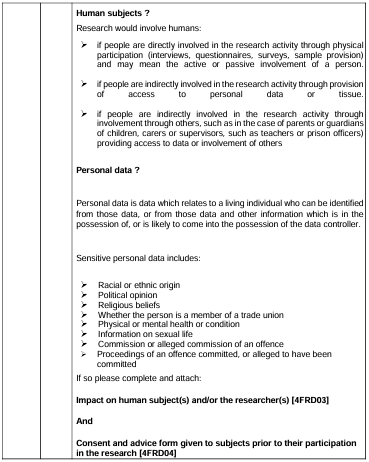

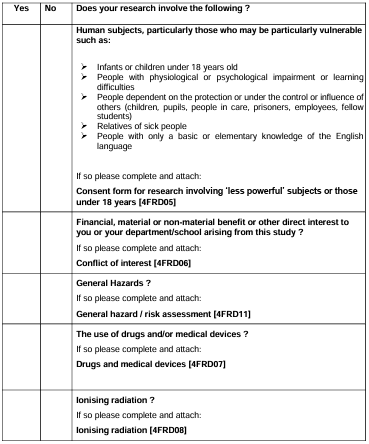

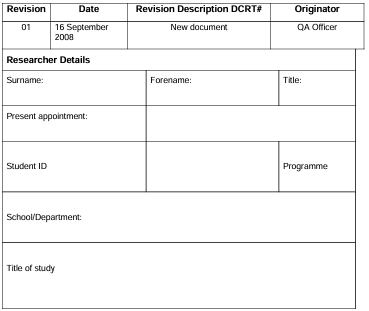

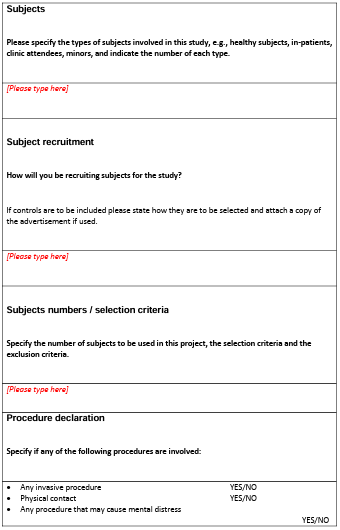

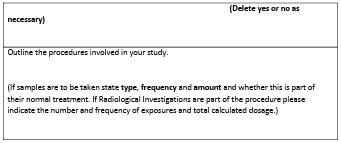

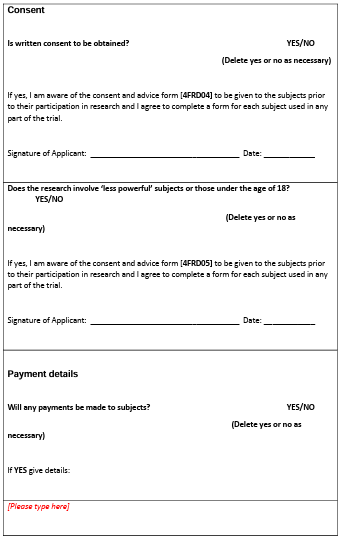

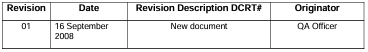

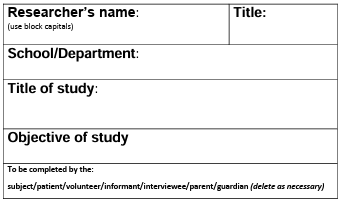

3.5 Ethical considerations ……………………………………………………………………..

3.6 Reflection ……………………………………………………………………………………..

3.7 Timeline ………………………………………………………………………………………..

3.8 Sampling ……………………………………………………………………………………….

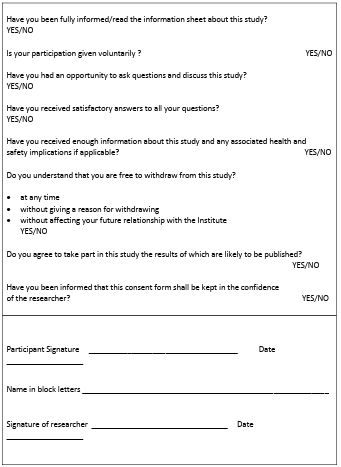

3.9 Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i2.0) accredited test of emotional intelligence …………………………………………………………………….

3.10 Method: Phase One ………………………………………………………………………..

3.10.1 Overview ………………………………………………………………………….

3.10.2 Pilot ………………………………………………………………………….

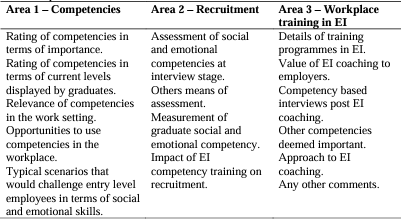

3.10.3 Employer Survey ………………………………………………………………………….

3.10.3.1 Survey Questions ………………………………………………………………

3.10.3.2 Survey design issue – Question 5 ………………………………………..

3.10.4 Semi -Structure Interviews ………………………………………..

3.10.4.1 Thematic Analysis …………………………………………………………….

3.11 Method Phase Two …………………………………………………………………………

3.11.1 Pilot …………………………………………………………………………

3.11.2 Recruitment of participants …………………………………………………………………………

3.11.3 Bar -on EQ-i 2.0 testing of research partcipant, one -to -one and group EI coaching …………………………………………………………………………

3.12 Method Phase Three ……………………………………………………………………….

3.12.1 Mock EI competency based interviews ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13 Method – Inferential statistics ………………………………………………………….

3.13.1 Exploratory versus confirm analysis ……………………………………………………………………….

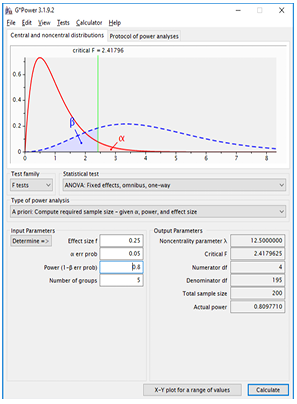

3.13.2 Statistical power ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.3 Null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.4 Type I and Type II errors ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.5 Effect Size ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.6 Bootstrapping ……………………………………………………………………….

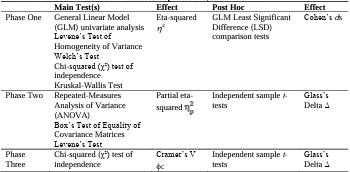

3.13 .7 Phase One tests ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.1 GLM ANOVA ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.2 Levene’s Test for Homogeneity of Variance ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.3 Welch’s Test ……………………………………………………………………….

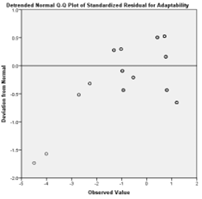

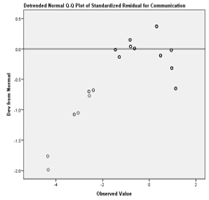

3.13.7.4 Residuals ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.5 Chi-Squared Test of Independence ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.6 Kruskal – Wallis H-Test ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.7.7 Eta-squared (η2) ………………………………………………………………..

3.13.7.8 Post Hoc Comparison Tests for GLM ANOVA …………………….

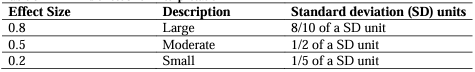

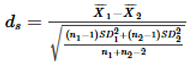

3.13.7.9 Cohen’s d/ds ……………………………………………………………………..

3.13.8 Phase Two Tests ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.8.1 Repeated-Measures ANOVA ……………………………………………..

3.13.8.2 Box’s Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices……………………..

3.13.8.3 Partial eta-squared ( ) ………………………………………………………

3.13.8.4 Independent samples t-tests ………………………………………………..

3.13.8.5 Glass’s Delta Δ …………………………………………………………………

3.13.8.9 Phase Three Test ……………………………………………………………………….

3.13.9.1 Chi-Squared Test of Independence ………………………………………

3.13.9.2 Cramér’s V (C) …………………………………………………………………

3.13.9.3 Independent samples t-tests ………………………………………………..

3.13.9.4 Glass’s Delta Δ …………………………………………………………………

3.14 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….

Chapter Four : Results Phase One ……………………………………………………………..

4.1 Overview ………………………………………………………………………………………

4.2 Main results: employer survey …………………………………………………………

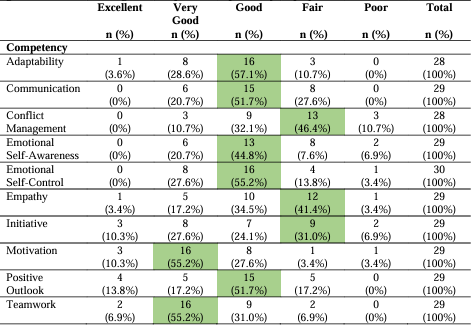

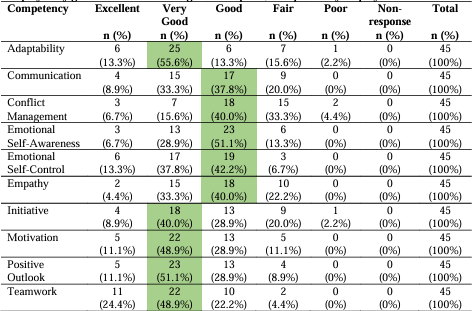

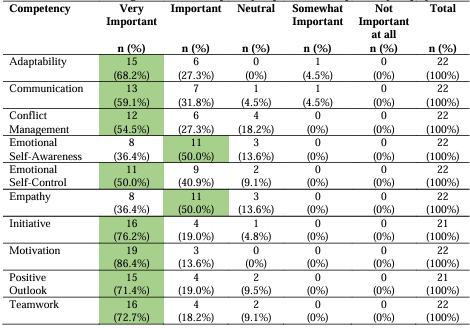

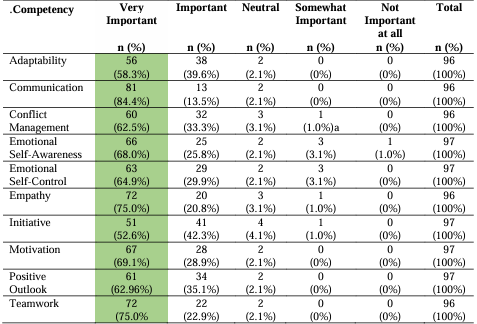

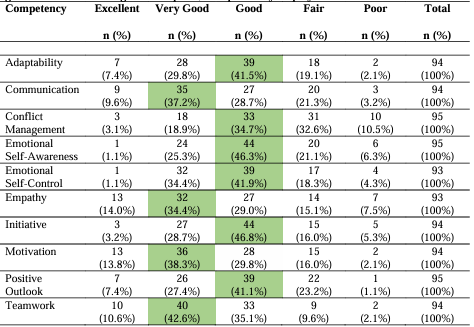

4.3 Employer responses – EI competency importance ………………………………

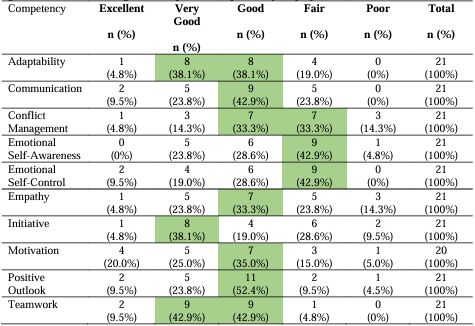

4.4 Employer responses – current levels of EI competence………………………..

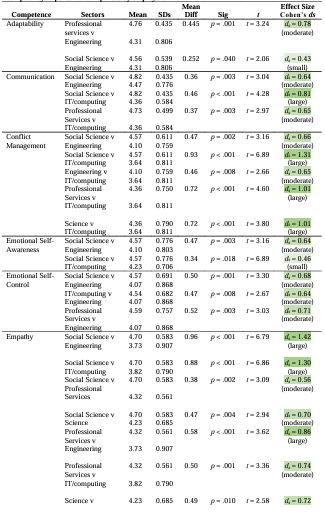

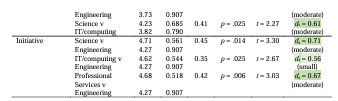

4.5 Responses by sector ………………………………………………………………………..

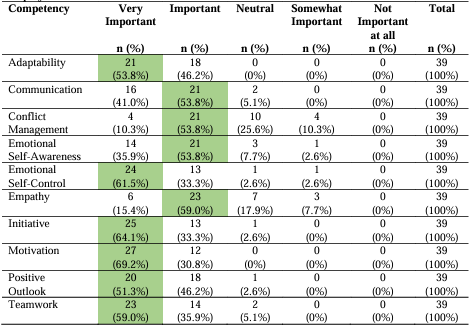

4.5.1 Engineering ………………………………………………………………………..

4.5.2 Information Technology/Computing ………………………………………………………………………..

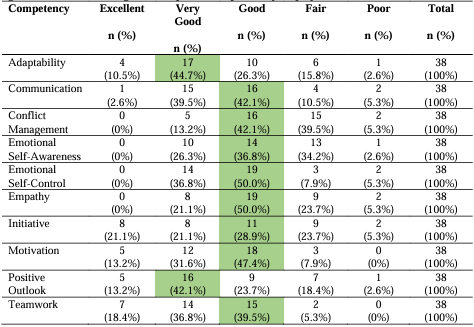

4.5.3 Professional Services ………………………………………………………………………..

(Accounting/Finance/Business/ HR/Law/ Retail)

4.5.4 Science (Including Pharmaceutical/Life) ………………………………………………………………………..

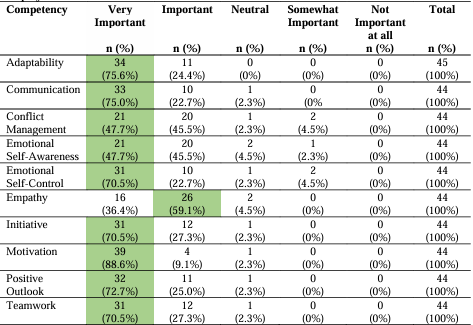

4.5.5 Social Science ………………………………………………………………………..

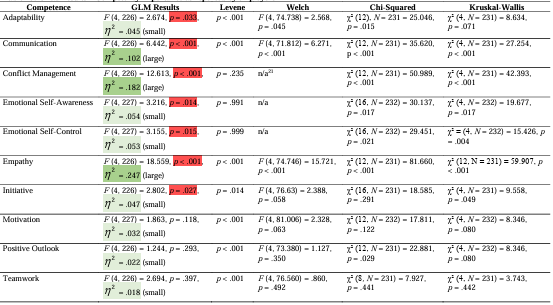

4.6 GLM univariate analysis – EI competency importance as reported by employers ………………………………………………………………………………………..

4.7 GLM univariate analysis: current levels of EI competency displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers ………….

4.8 Employer Survey: qualitative results…………………………………………………

4.8.1 EI and Professionalism …………………………………………………

4.8.2 Confidence …………………………………………………

4.8.3 Self -Awareness …………………………………………………

4.9 Phase One Results: Semi-structured interviews ………………………………….

4.9.1 Introduction …………………………………………………

4.9.2.1 Theme One: The changing workplace ………………………………….

4.9.2.2 Theme Two: The dynamic nature of the role ………………………..

4.9.2.3 Theme Three: EI and professionalism ………………………………….

4.9.2.3.1 EI, professionalism and peer interactions ……………………………

4.9.2.3.2 EI, professionalism and clients ………………………………………….

4.9.2.3.3 EI and compliance/regulation ……………………………………………

4.9.2.4 Theme Four: Issues with low levels of EI among graduates ……

4.9.2.4.1 Age, experience and upbringing ………………………………………..

4.9.2.4.2 Lack of preparation at third level ……………………………………….

4.9.3 Topic Two : Recruitment ……………………………………….

4.9.3.1 Theme One: CV and Interview Preparation ………………………….

4.9.3.2 Theme Two: Diverse measurements of EI competence by employers …………………………………………………………………………

4.9.3.2.1 Assessment Centres …………………………………………………………

4.9.3.2.2 Online Code Tests ……………………………………………………………

4.9.3.2.3 Competency based interviews …………………………………………..

4.9.3.3 Theme Three: Demonstration of EI as an influencing factor on

graduate hire …………………………………………………………………….

4.9.3.4 Theme Four: Diversity in terms of EI coaching …………………….

4.9.3.4.1 Team based activities ……………………………………………………….

4.9.3.4.2 Role Plays and Scenarios ………………………………………………….

4.9.3.4.3 Video ……………………………………………………………………………..

4.9.3.4.4 Case Studies ……………………………………………………………………

4.9.4 Topic Three: Workplace training in EI ……………………………………………………………………

4.9.4.1 Theme One: Employer investment in graduates …………………….

4.9.4.1.1 Training ………………………………………………………………………….

4.9.4.1.2 Mentors/Coaches …………………………………………………………….

4.9.4.1.3 Presentations …………………………………………………………………..

4.9.4.1.4 Project Teams …………………………………………………………………

4.9.4.1.5 Internships ………………………………………………………………………

4.9.4.1.6 Counselling …………………………………………………………………….

4.10 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….

Chapter Five : Results Phase Two ………………………………………………………………

5.1 Overview ………………………………………………………………………………………

5.2 Main findings: research question three ……………………………………………..

5.3 Descriptive Statistics ………………………………………………………………………

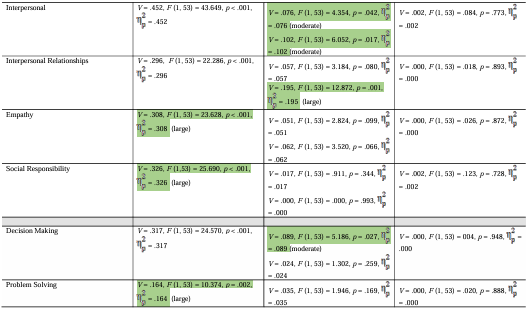

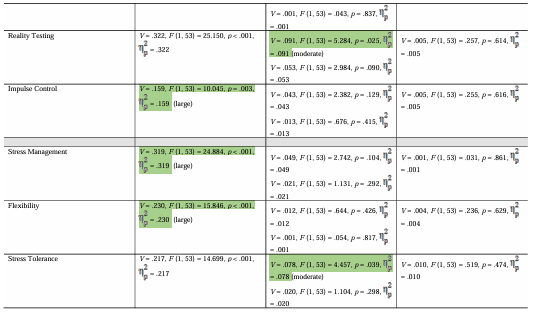

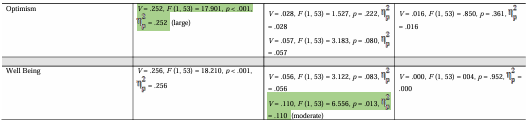

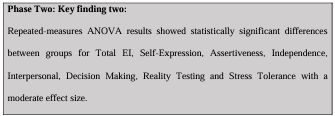

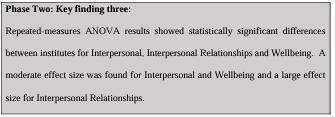

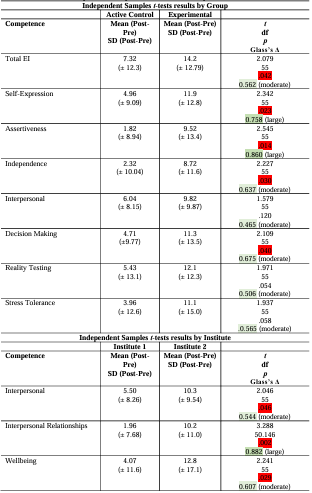

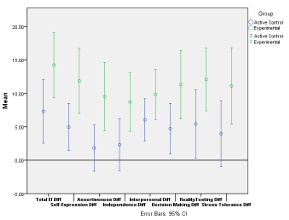

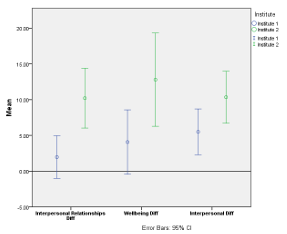

5.4 Repeated-measures ANOVA……………………………………………………………

5.5 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….

Chapter Six : Results Phase Three ……………………………………………………………..

6.1 Overview ………………………………………………………………………………………

6.2 Main Results: Mock EI interview rating sheets ………………………………….

6.2.1 Chi-squared(x2)results ……………………………………………………………..

6.2.2 Post Hoc Independent sample t-test results ……………………………………………………………..

6.3 Phase Three – Qualitative results ………………………………………………………

6.3.1 Theme One: Importance of identifying and articulating Weaknesses ……………………………………………………..

6.3.2 Theme two :Self-Awareness ……………………………………………………..

6.3.3 Theme three: EI and teamwork ……………………………………………………..

6.3.4 Theme four : EI and work experience ……………………………………………………..

6.3.5 Theme five : EI as a critical factor in determining employability ……………………………………………………..

6.3.6 Theme six : Behavioural Dispositions as key to graduate hire ……………………………………………………..

6.3.7 Theme seven : Interview Preparation ……………………………………………………..

6.4 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….

Chapter Seven : Discussion, Strengths, Limitations, Future Research, Conclusions ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

7.1 Overview ………………………………………………………………………………………

7.2 What are the emotional and social (EI) skills that Irish employers deem important for graduates to possess in five sectors of the Irish economy? ….

What are the current levels of EI being displayed by graduates, when entering the workplace, as reported by employers in these sectors?…………

7.2.1 Self -awarencess as key to success in the workplace …………………………………………………………..

7.2.2 Diversity in terms of culture in the workplace …………………………………………………………..

7.2.3 EI Conching as an effective means for promoting social and emotional competency …………………………………………………………..

7.2.4 Importance of EI in the recruitment process …………………………………………………………..

7.2.4.1 Assessment Centres …………………………………………………………..

7.2.5 EI and employability …………………………………………………………..

7.3 Does a tailored, as opposed to a general approach to social-emotional competency coaching for final year engineering students, based on the stated needs of employers, result in different group mean EQ-i2.0 scores

post-intervention? ……………………………………………………………………………..

7.4 Are students who received tailored, as opposed to general EI coaching rated differently by employers with respect to their knowledge of EI, the application of EI to the workplace and employability?……………………..

7.4.1 Behavioural disposition as key to graduate hire ………………………………………………………..

7.4.2 EI development through curricula ………………………………………………………..

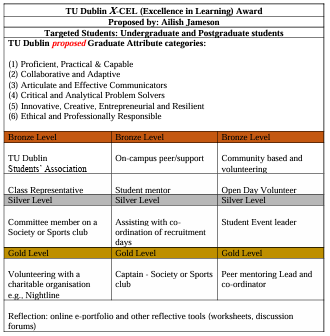

7.4.3 Template for TU Dublin X-Cel (Excellence in personal Development) Award ………………………………………………………..

7.4.4 EI development through employability workshops ………………………………………………………..

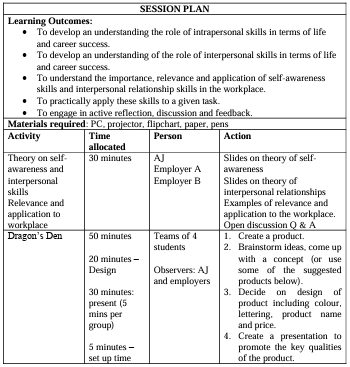

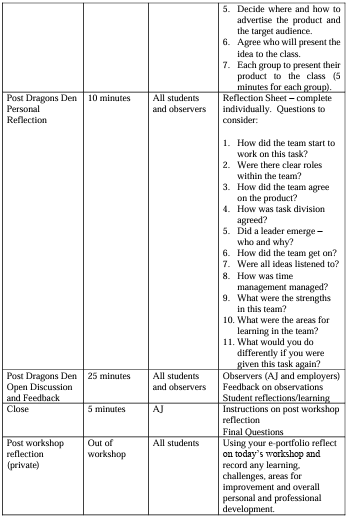

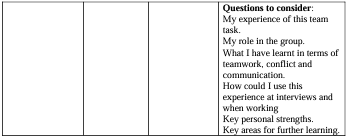

7.4.5 The Employability Workshop Series Workshop No .1 ………………………………………………………..

7.5 Critical evaluation of the study ………………………………………………………..

7.6 Strengths of the study ……………………………………………………………………..

7.7 Limitations of the study …………………………………………………………………..

7.8 Future Research ……………………………………………………………………………..

7.9 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………….

References………………………………….………………………………………….

List of Publications…………………………………………………………………….

Appendices………….…………………………………………………………….……

Declaration

I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Social-Emotional Intelligence (EI), graduates and the workplace – A study of a tailored approach to EI competency development for final year engineering students” submitted to TU Dublin – Blanchardstown campus for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other third level institution. I also certify that the work described here is entirely my own or has been referred to in the text.

_____________________________ _______________

Ailish Jameson Date

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the enormous support and guidance given to me by my supervisory team of Dr Aiden Carthy, Dr Colm McGuinness and Dr Fiona McSweeney. Their commitment, input and expertise were invaluable to me throughout the research process. Thanks to the employers and final year engineering students who participated in this research and gave so generously of their time. Thanks to all the staff in both Institutes of Technology (IOTs) for their support. Particular mention to the Head of Mechanical Engineering in Institute 2 and to the student representatives in the two IOTs for all their help in the co-ordination aspects of phases two and three. I also wish to acknowledge funding received from the TU Dublin Programmes for the Future fund.

Special thanks to my friends and family who supported me throughout the PhD journey, in particular, enormous love and gratitude to my inspirational sons Aaron and Ken Heery.

I wish to dedicate this work to my father-in-law Seán Heery, the kindest, most generous and probably the most intelligent man I have ever met. He supported and guided me in my life and throughout my academic career but sadly departed this world in April, 2018. Huge gratitude for everything you did for me.

“I have no special talent; I am just passionately curious”

(Albert Einstein)

Abstract

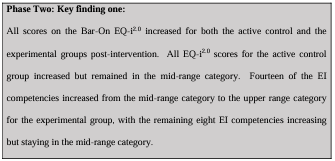

Previous research has demonstrated that higher social and emotional competence (EI) results in increased life and career success. To date, EI coaching programmes have been delivered in higher education and in the workplace and have demonstrated success in terms of increased EI competence, post intervention. However, to date no attempt has been made in an Irish context to design and deliver a tailored EI coaching programme, based on the stated needs of employers. This study aimed to address this gap in EI research. It was exploratory in nature with a mixed method design being employed. In Phase One, a survey of employers in key vocational sectors of Irish industry was conducted to gather their opinions on (i) the importance of EI competencies and (ii) the current levels being displayed by graduates, on entering the workplace. Phase One concluded with a series of semi-structured interviews with employers (n = 5). Based on these results and due to the iterative nature of the research, a sample of final year engineering students (n = 62) in two institutes of technology (IOTs) in Dublin were recruited to participate in Phase Two. Participants were tested at baseline utilising an accredited test of EI, the Bar-On EQ-i2.0 and one general and one bespoke EI coaching programme were designed and delivered. In Phase Three, each participant met with an employer for a mock EI competency based interview, followed by post-intervention testing. Key results demonstrated that employers rated all competencies as either ‘very important’ or ‘important’, with highest ratings of ‘good’ being attributed to current levels among graduates. Scores on the EQ-i2.0 increased for both groups, post-intervention with statistically significant differences found between the groups for some of the competencies. A template for a TU Dublin X-Cel (Excellence in Personal Development) award has been designed based on results from this study.

List of Tables

Table 1: TEIQue ……………………………………………………………………………………………

Table 2: Four Branch Model of EI …………………………………………………………………..

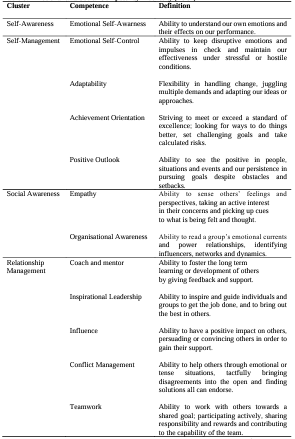

Table 3: Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI) ……………………………

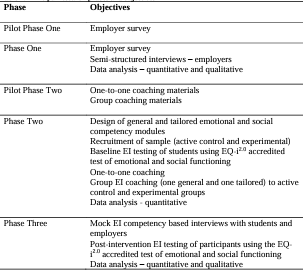

Table 4: Principal research phases and objectives ……………………………………………

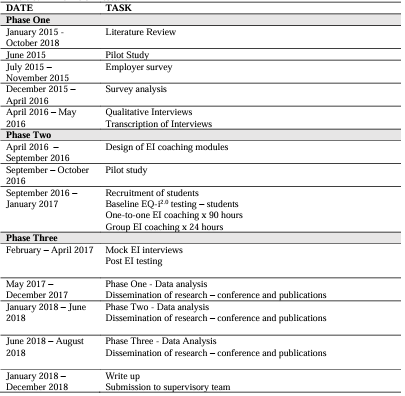

Table 5: Timeline of Research ……………………………………………………………………..

Table 6: Topic Guide: Semi-structured interviews …………………………………………..

Table 7: Group EI coaching by Group ……………………………………………………………

Table 8 Breakdown of statistical tests used in phases one, two and three …………..

Table 9: Cohen’s d effect size – interpretation …………………………………………………

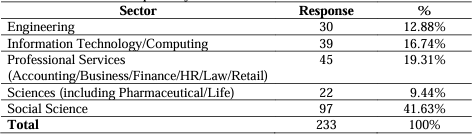

Table 10: Breakdown of responses by sector …………………………………………………..

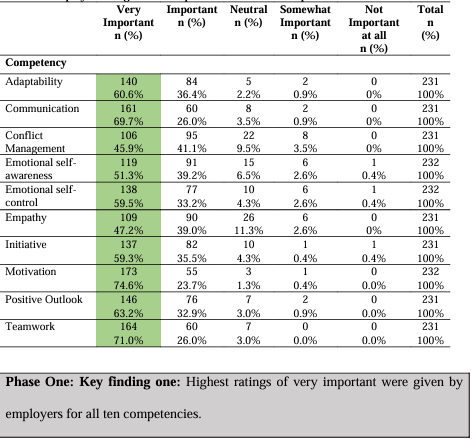

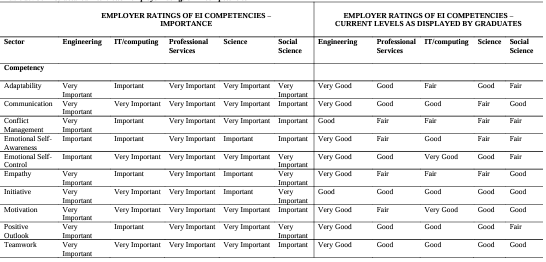

Table 11: Employer ratings of EI competencies in terms of importance ……………..

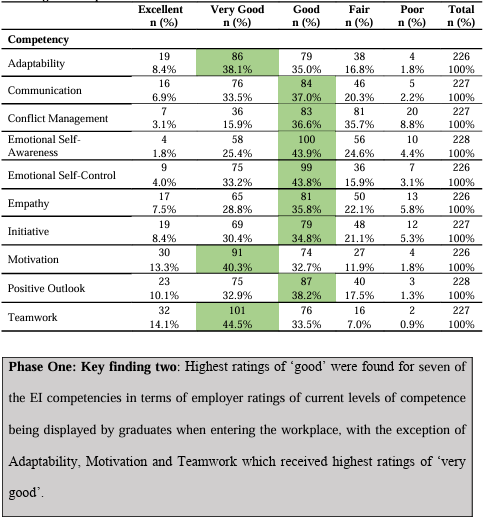

Table 12: Employer ratings of current levels of competence being displayed by graduates, when entering the workplace …………………………………………………………

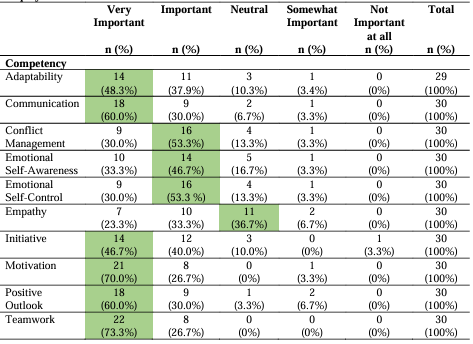

Table 13: Engineering – ratings in terms of competency importance, as reported by employers ………………………………………………………………………………….

Table 14: Engineering – ratings in terms of current level of competence being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers …

Table 15: IT/computing – ratings in terms of competency importance, as reported by employers ………………………………………………………………………………….

Table 16: IT/computing – ratings in terms of current level of competence being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers …

Table 17: Professional Services – ratings in terms of competency importance, as reported by employers ………………………………………………………………………………….

Table 18: Professional Services – ratings in terms of current level of competence being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers …………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Table 19: Science – ratings in terms of competency importance, as reported by employers …………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Table 20: Science -ratings in terms of current level of competence being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers …

Table 21: Social Science – ratings in terms of competency importance, as reported by employers ………………………………………………………………………………….

Table 22: Social Science – ratings in terms of current level of competence being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace, as reported by employers …

Table 23: GLM Results – Competency importance as reported by employers …….

Table 24: Summary of statistically significant GLM post hoc comparisons using LSD in terms of competency importance as reported by employers…………..

Table 25: GLM Results – current levels of competence displayed by graduates as reported by employers ……………………………………………………………………………..

Table 26: Summary of statistically significant GLM post hoc comparison using LSD in terms of current levels displayed by graduates as reported by employers ..

Table 27: Semi-structured interviews – employer ratings of EI competencies …….

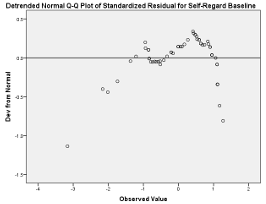

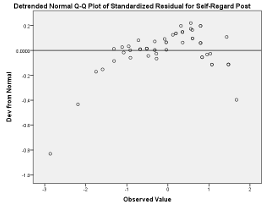

Table 28: Means, standard deviations, mean differences and standard errors for baseline and follow-up scores for participating students in each EQ-i2.0 domain and sub-category by group ……………………………………………………………………………

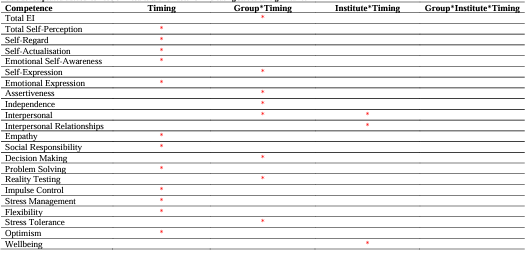

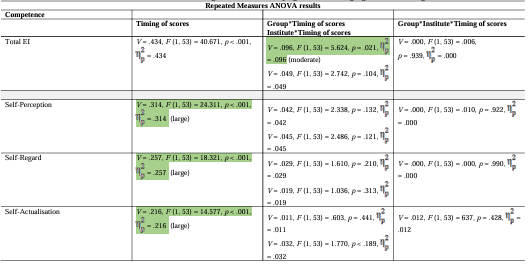

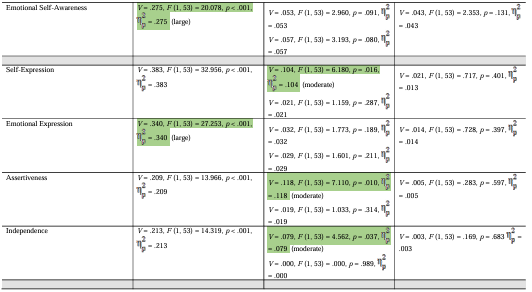

Table 29: Repeated-Measures ANOVA results with an asterisk indicating statistical significance ………………………………………………………………………………….

Table 30: Detailed model terms and associated effect sizes, with highest order statistically significant terms highlighted in shades of green……………………………..

Table 31: Post-Hoc Independent Samples t-test results – Group and Institute ……..

Table 32: Mock EI competency based interviews – employer responses …………….

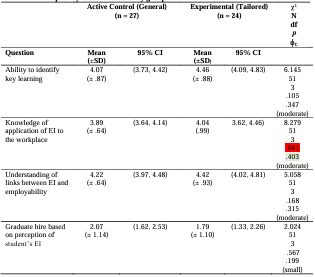

Table 33: Means, standard deviations, confidence intervals, χ², df, significance Cramer’s V (C) for mock EI competency based interviews by group ………………..

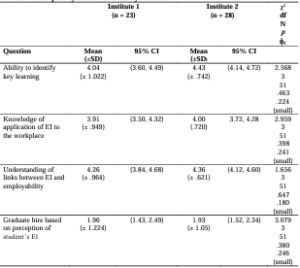

Table 34: Means, standard deviations, confidence intervals, χ², df, significance Cramer’s V (C) for mock EI competency based interviews by institute …………….

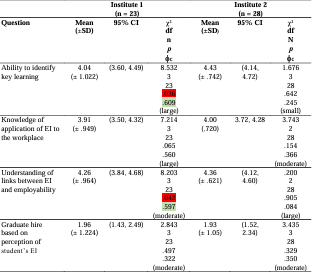

Table 35: Means, standard deviations, confidence intervals, χ², df, significance Cramer’s V (C) for mock EI competency based interviews split by institute ………

List of Figures

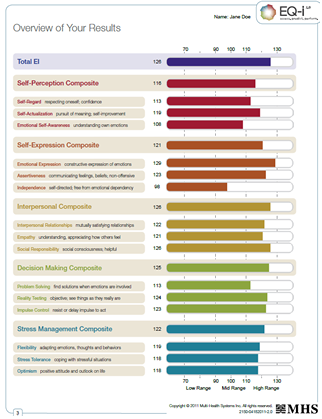

Figure 1: Bar-On EQ-i2.0 model ………………………………………………………………………

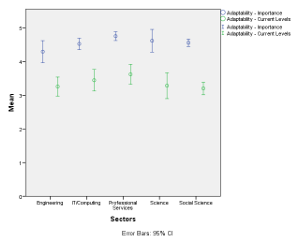

Figure 2: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Adaptability ……………………….

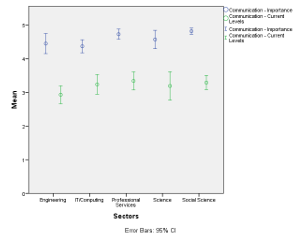

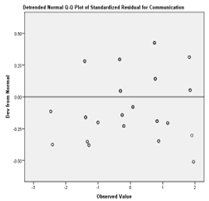

Figure 3: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Communication ………………….

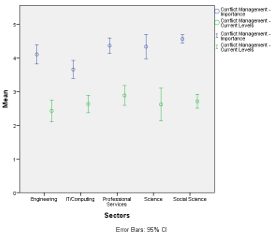

Figure 4: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Conflict Management ………….

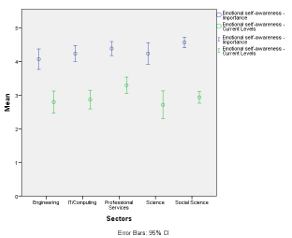

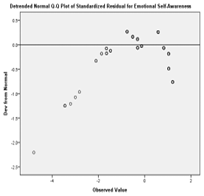

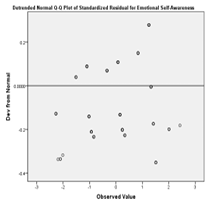

Figure 5: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Emotional Self-Awareness …..

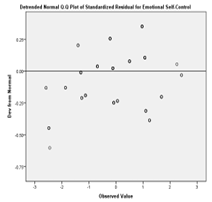

Figure 6: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Emotional Self-Control ……….

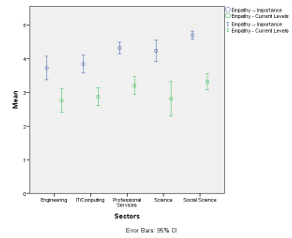

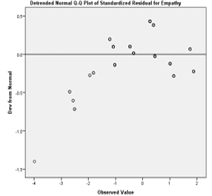

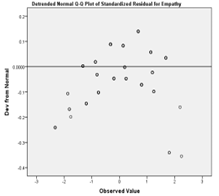

Figure 7: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Empathy ……………………………

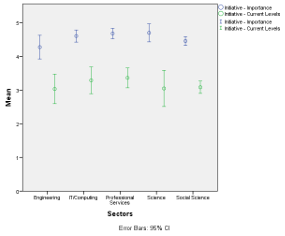

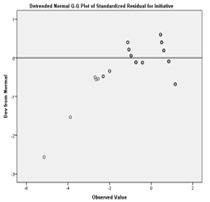

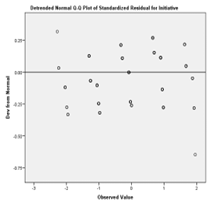

Figure 8: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Initiative ……………………………

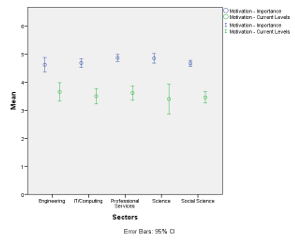

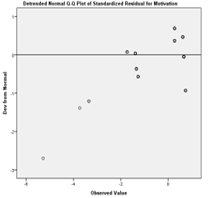

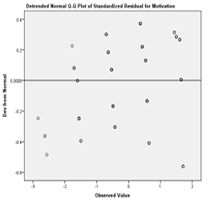

Figure 9: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Motivation …………………………

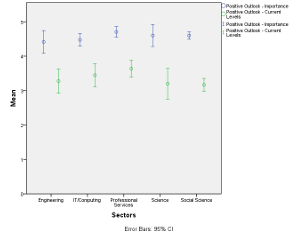

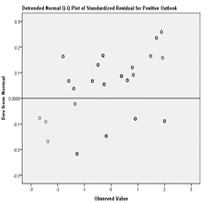

Figure 10: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Positive Outlook …………………

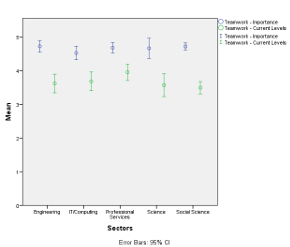

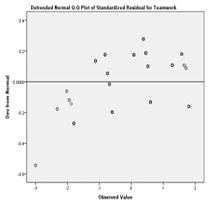

Figure 11: Comparison of mean ratings in terms of importance and current levels being displayed, as reported by employers – Teamwork………………………….

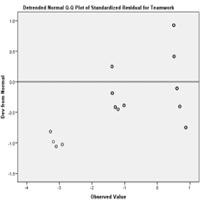

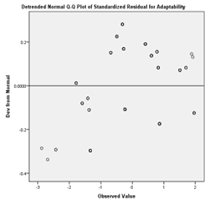

Figure 12: Difference scores for repeated-measures ANOVA statistically significant results by group …………………………………………………………………………..

Figure 13: Difference scores for repeated-measures ANOVA statistically significant results by institute ……………………………………………………………………….

Figure 14: Student ability to identify key EI learning ………………………………………

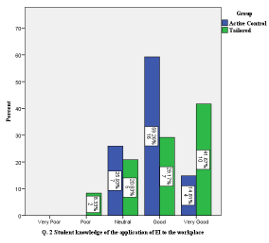

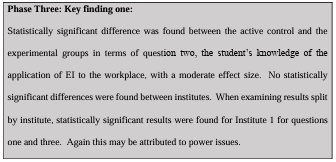

Figure 15: Student knowledge of the application of EI to the workplace …………….

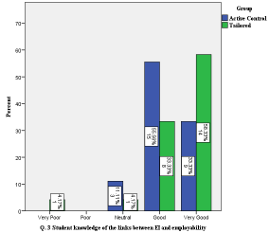

Figure 16: Student knowledge of the links between EI and employability ………….

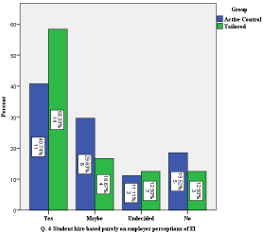

Figure 17: Student hire based purely on employer perceptions of EI ………………….

Chapter One: Introduction and Overview

1.1 Introduction

This chapter will present a brief overview of higher education, will outline the aims and objectives of the research and present the research questions. It will then discuss social-emotional (EI) competence, examine tailored versus general coaching and the links between EI coaching and employability. Finally, it will present a breakdown of the structure of the thesis.

1.2 Overview of higher education

In Ireland, higher education is provided by a number of universities, institutes of technology and colleges of education (Department of Education and Skills website n.d.). In addition, there are a number of third level institutions which provide specialist education in the fields of art and design, medicine, business studies, rural development, theology, music and law. The Higher Education Authority (HEA) is the statutory planning and development body for higher education and research in Ireland. The Universities Act, (1997) outlined the objectives and functions of a university, setting out the role and structure of governing bodies, staffing, academic councils and other duties. The HEA has an overseeing role in terms of such plans and quality assurance processes, while respecting the autonomy of each university. The Institutes of Technology Act, (2006) provided a similar template as the Universities Act, (1997) with the HEA acting in a comparable capacity. In Ireland, in 1960, 5% of 18 year olds progressed to higher education, by 1980, this had increased to 20% and currently it has risen to 65% (Department of Education of Skills, 2011). Critical to the role of higher education in Ireland is its ability to “add to the understanding of, and hence the flourishing of, an integrated social, institutional, cultural and economic life” (Expert Group on Future Funding for Higher Education, 2015, p. iii). Higher education shifted and changed from a linear process where new knowledge drove innovation in industry to a focus on four overlapping and interlinking “spheres” (Expert Group on Future Funding for Higher Education, 2015, p. iii). These are: university, business, government and civil society that seek to address “the complex economic, technical, social and environmental challenges” prevalent in modern society (p. iii).

The annual funding cost of higher education is approximately €2.7 billion, with the State providing 74% of such funding. According to the Expert Group, in publically funded higher education institutions, State funding has been reducing since 2008 with the introduction of student contributions and reduced student grants. When examining the purpose and value of higher education, the Expert Group argued that higher education should (i) provide a high quality student experience, (ii) support economic, social and cultural innovation, (iii) develop knowledge and capabilities of graduates which meet the expanding needs of the economy, society and public system, and (iv) be equitable in terms of access. This was echoed in the National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 report which argued that higher education should equip graduates with discipline specific knowledge, together with important skills, such as adaptability, creativity, “rounded” thinking and citizenship (Department of Education of Skills, 2011, p. 11). The National Strategy questioned the “right” skills required for both the graduates of 2015 and of 2030 and, once determined, asked how the correct combination of skills could be included as learning outcomes in higher education (p. 35). One recommendation was the need for higher education to shift from simply focusing on the “over-specialisation” of graduates in discipline specific knowledge to a move towards a more broad perspective to include core skills of quantitative reasoning, critical thinking, communication, teamworking and effective use of information technology (p. 35).

The National Strategy emphasised that higher education must be “excellent, relevant and responsive” to students’ personal development and growth, guiding them to be fully “engaged” citizens in society (Department of Education and Skills, 2011, p. 27). The skills of communication, teamworking, personal development and citizenship emphasised by the National Strategy report are all EI skills, marking an important change in higher education teaching and practices. In recent years, a shift has taken place in many technical disciplines from purely teaching technical knowledge to a focus on social and emotional competency development (Ilyasova, 2015). For example, in engineering the role of emotions in terms of projects, productivity and wellbeing have increasingly become more important. While it is accepted that technical skills are critically important, there is growing recognition of the need for high levels of EI competency in this discipline as, according to Fasano, (2013), EI can be the difference between a good engineer and a great engineer.

1.3 Aims and objectives

The principal aim of this research was to explore whether a tailored approach, as opposed to a general approach to social-emotional (EI) coaching, based on the stated needs of employers, resulted in different mean Bar-On EQ-i2.0 scores post intervention. The Bar-On EQ- i2.0 test of EI will be discussed in greater detail later in the review. To date, no research exploring the opinions of employers on the importance of EI competency when transitioning into the workplace has taken place, in an Irish context. This study was conducted in two IOTs in Dublin. The researcher is a former student of one of the IOTs and had worked there on a part-time basis as an Assistant Lecturer in the School of Humanities. The specific objectives of this study were:

1. To conduct a survey of the opinions of employers in five sectors of the Irish economy: engineering, IT/computing, professional services, science and social science, as to the social and emotional skills that they deemed important for graduates to possess as well as the current levels being displayed by graduates when entering the workplace.

2. To conduct a series of semi-structured interviews with employers to gather detailed data on EI competency in the workplace and to obtain their input on the design and delivery of a bespoke EI coaching programme.

3. To administer the Bar-On EQ-i2.0 pre and post intervention to final year engineering students across the two IOTs.

4. To design and deliver one-to-one individualised EI coaching to final year engineering students using the workplace report generated by the Bar-On EQ-i2.0. The design of the one-to-one coaching for the tailored group incorporated elements of employer feedback from objective 2.

5. To design and deliver (i) a general group EI coaching programme based on established programmes already delivered in the workplace and (ii) a bespoke group EI coaching programme tailored to the specified needs of employers, aimed at increasing specific emotional and social skills associated with employability.

6. To conduct one-to-one mock EI competency based interviews between final year engineering students and employers to determine if a discipline specific approach to EI competency development as opposed

to a general approach resulted in enhanced EI knowledge, employability and graduate hire, from the employer’s viewpoint.

1.4 Research questions

Based on the objectives outlined above, this research addressed the following four principal research questions:

1. What are the emotional and social (EI) skills that Irish employers deem important for graduates to possess in five sectors of the Irish economy?

2. What are the current levels of EI being displayed by graduates, when entering the workplace, as reported by employers in five sectors of the Irish economy?

3. Does a tailored, as opposed to a general approach to social-emotional competency coaching for final year engineering students, based on the stated needs of employers, result in different group mean EQ-i2.0 scores post intervention?

4. Are students who received tailored, as opposed to general EI coaching rated differently by employers with respect to their knowledge of EI, the application of EI to the workplace and employability?

The research questions will now be discussed, with a particular focus on the rationale underpinning each.

1.5 Social-emotional (EI) competency in the workplace – importance and current levels

In recent decades, EI has become increasingly important in the workplace and has been linked with many critical skills such as teamwork, communication, flexibility and adaptability and has been reported to account for 58% of job performance across all sectors of employment (Bradberry & Greaves, 2009). Poor EI has been identified as one of the top five reasons that new hires fail, according to Arcement, (2018). According to Platt, (2015), EI is a key factor in terms of career and life success with low levels of EI being reported to result in challenges in the workplace and, in some cases, careers being jeopardised. Platt, (2015) further argued that poor EI in the workplace is often manifested by an inability to convey ideas, issues with working in teams and gaining trust, and difficulties understanding other people’s emotions. In an educational context, intelligence quotient (IQ) is important in terms of technical knowledge and know-how, however, it is the social and emotional factors which influence success at college (Cherniss, 2000b). According to Hughes and Barrie, (2010), the development of personal transferable skills such as self-responsibility, compassion, capability, self-awareness and cultural awareness are critically important elements of an undergraduate education.

With the shift in the emphasis in higher education to market driven objectives, higher education institutions are now expected to design and deliver an employability agenda (Findlow, 2008). Graduate employability was a key focal point of the Bologna process with a core aim being the examination of skills deficits and measures to address such deficits. To date, many EI coaching interventions have been delivered in the workplace targeting specific EI competencies. However, no research has been undertaken, in an Irish context to survey and interview employers to gather their opinions on (i) the importance of EI in the workplace, (ii) the current levels being displayed by graduates, when entering the workplace and (iii) the design and delivery of a bespoke EI coaching programme. Therefore, this research was the first of its kind in an Irish context to adopt a collaborative process with employers throughout the research process. This research was particularly timely as, in January, 2018 the Institute of Technology, Blanchardstown (ITB) merged with the Institute of Technology, Tallaght (ITT) and Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) to become Ireland’s first Technological University, TU Dublin. TU Dublin has a particular emphasis on employability and ensuring graduates are career and life-ready (TU Dublin, 2014). Accordingly, this research yielded valuable data in terms of graduate attribute and employability skills required by employers in today’s workplace which could be utilised to inform interventions for students in the newly established TU Dublin.

1.6 Tailored versus general EI coaching

Previously, attempts have been made at designing and delivering tailored EI coaching in higher education and in the workplace. Carthy (2013) examined EI in terms of student engagement and attrition levels and delivered individualised coaching to participants, resulting in a decrease of just under one third in the attrition rate for students who received coaching. American Express delivered a programme to its financial advisers with the focus being on one EI competency; emotion management (Lennick, 2007). The EQ-i (revised to the EQ-i2.0 in 2011) was administered to all its financial advisers and a control and experimental group assigned, with the control group receiving no intervention. Participants in the experimental group reported less stress and an 18% rise in sales was found in this group. In another study conducted by Lopes, Grewal, Kadis, Gall and Salovey, (2006) the focus was on the association between EI and work performance. A sample of 44 analysts and clerical staff aged between 23 and 61 years of age from a finance department of a Fortune 400 insurance company participated. The study adopted a multi-rater feedback design and utilised the Bar-On 360 EI test which will be explained in more detail in Chapter Two. Some of the findings demonstrated that EI was positively linked with percent merit increase and rank but not salary. It was also related to peer rated indicators of interpersonal facilitation, interpersonal sensitivity, sociability and contribution to positive work environment and peer rated mood. The ‘Search Inside Yourself’ EI coaching programme was delivered to engineers within Google and targeted many EI competencies linked with workplace performance and success, in particular, self awareness, motivation and teamwork (Tan, 2012). Some of the results reported by participants were less emotional drain following the programme, reduced stress and general improvements in wellbeing. What was unique in the current study was the inclusion of employers in guiding the design and delivery of the EI coaching process.

1.7 EI coaching and employability

In recent years, graduate employability and pathways to employment following graduation have been the subject of much debate. Employability was included in the four pillars of the European Employment Strategy and was a defining theme of the Extraordinary European Council on Employment which was held in Luxembourg in 1997 (European Union, 2010). The European Employment Strategy was revised in 2003 and employability was broadened to include a focus on (i) employment for all, (ii) high quality and productivity at work and, (iii) an inclusive labour market. Globalisation has led to significant changes in the nature of the workplace with an increasing demand for EI competency in order to successfully transition from higher education into the workplace, according to Emmerling, Shanwal and Mandal, (2008). Employability was a key feature of this study, in particular, in Phase One and Phase

Three. Specifically in Phase Three employers conducted one-to-one mock EI competency based interviews where they rated participants in terms of their key learning from the EI coaching process, their ability to apply the learning into the workplace and make important links between EI and employability. Ultimately, this phase sought to determine who was more successful in terms of hire, the active control or the experimental group.

1.8 Structure of the thesis

This study is contextualised within a multiple intelligence (MI) theoretical framework which adopts a pragmatic approach to how intelligence is defined (Hoerr, 2000). An MI framework contends that intelligence is a multi-faceted, complex capacity which includes both cognitive intelligence (IQ) and social and emotional competency (Hoerr, 2000). Chapter Two begins by presenting a review of the literature. It is divided into three sections. Section One focuses on the historical evolution of EI and examines emotion and intelligence as two separate constructs and charts the evolution of multiple intelligences with a specific focus on personal intelligences. Section Two examines EI and higher education and discusses the changing landscape of higher education from one focused solely on academic achievement to an environment which promotes personal development, social and emotional competency development and citizenship behaviour. The term employability is examined, with a specific focus on how policy documents such as the Bologna Declaration on the European Space for Higher Education and the National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 have impacted on higher education. Section Three focuses on EI, graduates and the workplace and examines coaching and the theory and principles of EI coaching. It discusses EI coaching interventions in the workplace utilised to develop and enhance work performance.

Chapter Three outlines and justifies the ontological and epistemological approaches that were utilised in this research and presents details of the pilot study conducted prior to the principal intervention taking place. This chapter also presents a detailed outline of the methodology used to address the research objectives, including a discussion of ethical issues relevant to this study and a description of the steps that were taken to ensure that ethical standards were maintained throughout the research process. It also details the inferential statistics that were utilised in phases one, two and three of this study and the analysis process of all data, both quantitative and qualitative.

Chapter Four presents the results from Phase One of the study. Phase One was mixed as both qualitative and quantitative data was gathered. SPSS Version 24 was utilised to analyse quantitative data and thematic analysis was used for analysis of the semi-structured interviews. Chapter Five presents the results from Phase Two of the study. Phase Two was quantitative in nature and utilised SPSS to analyse the baseline and post-intervention Bar-On EQ-i2.0 test scores. Chapter Six presents the results from Phase Three of the study. Phase Three adopted a mixed approach as Likert scale data was gathered and analysed using SPSS and thematic analysis was used to analyse qualitative data.

Chapter Seven presents a synthesis of the findings and discusses them in relation to existing literature on EI and the workplace, the development of graduate attributes and workplace based EI coaching. It re-examines the primary research questions and discusses the research findings with respect to the literature concerning EI and the workplace, graduate attribute development and EI coaching initiatives already delivered in the workplace. Based on the results from this study, a template for a TU Dublin X-Cel (Excellence in Personal Development) award was designed and is outlined. In addition, a sample of an EI employability workshop that was designed as part of an employability series is included. This final chapter also discusses the strengths and limitations of the research and some key recommendations for future research as well as future implications of this research.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1 Section One: Historical Evolution of EI

2.1.1 Introduction

Many theorists claimed that in the 20th century the “driving force of intelligence” was IQ but for the 21st century it will be social and emotional intelligence (EI) (Mann, 2012; Zeidner, Matthews, & Roberts, 2004, p. 379). When focusing on its application in third level education, Cherniss, (2000b) held that IQ was important in terms of knowledge, skills and the ability to complete educational tasks, however, it was social and emotional factors which influenced success at college. When expanding this idea in terms of the workplace, it is accepted that technical skills and education are critically important, however, interpersonal skills, motivation to produce and working collaboratively are important elements in workplace success (Ngonyo Njoroje, & Yazdanifard, 2014). According to Bradberry and Greaves, (2009) EI is the basis for an extensive range of critical skills required in the workplace and accounts for 58% of job performance across all sectors of employment. Cherniss, (2000a) held that while cognitive ability and non-cognitive ability are related, cognitive ability plays a limited role in terms of life success. The question remains as to the relative impact of IQ and EI in determining such success. There have been challenges in defining and conceptualising EI, however, there is agreement that EI covers “an array of emotional functions” (Zeidner et al., 2004, p. 373). Mayer and Salovey, (1997, p. 10) proffered that EI was:

“the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth”.

A more recent definition by Stein and Book, (2011, p. 14) expands on the concept of EI to include a survival aspect as well as its impact on overall functioning. The authors stated that “EI is a set of skills that enables us to make our way in a complex world – the personal, social and survival aspects of overall intelligence, the elusive common sense and sensitivity that are essential to effective daily functioning”. Prior to developing the discussion on EI, it is important to examine the evolution of intelligence from purely a focus on cognitive intelligence to one which included social intelligence followed by emotional intelligence. Different elements were involved in the expansion of this construct including (i) emotion, (ii) emotion and the brain and (iii) intelligence itself, which will now be discussed.

2.1.2 Emotion

According to Lazarus, (1991, p. 6) emotion is a “psychosocialbiological construct”, a combination of motivation, cognition, adaptation and physical elements which form part of a single state requiring in-depth analysis. Emotions are “complex, patterned, organismic reactions to how we think we are doing in our lifelong efforts to survive and flourish and to achieve what we wish for ourselves” (p. 6). Emotions are often described as a “higher order of intelligence” (Caruso, 2008, p. 4). Shiota and Kalat, (2012) held that there are four elements of emotion, (i) cognition/appraisal, (ii) feelings, (iii) physiological changes, and (iv) behaviour. Although linked, there was no set agreement as to how the elements “hang together” (p. 26). In the late 1800s, the James-Lange Theory of Emotion was developed which argued that emotions were labels attributed to bodily responses in particular situations. It was believed that responses to life events were sequenced, i.e., an event occurred which resulted in a physiological change, leading to a corresponding behaviour, followed by an emotion. In the 1920s and 1930s, Cannon, cited by Shiota & Kalat, (2012) discovered that the sympathetic nervous system was responsible for fight or flight reactions. The Cannon Bard Theory followed which argued that responses of the muscles and organs were too slow to have any role in the feeling element of emotion and that “emotional cognitions and feelings” were independent from “physiological arousal and behaviour” despite all four elements happening at the same time (Shiota and Kalat, 2012, p. 14).

According to Ferguson (2000, p. 83), in 1902, Wundt identified key links between emotion and arousal and held that a dimensional approach to describing emotion was best, describing feelings as being “discrete”. Wundt identified a link between emotion and cognition and argued that for every emotional experience, a new set of cognitive thoughts was created in conjunction with physical changes, leading to action being taken. One significant finding was that many different emotions produced similar physical responses. In addition, Watson – the psychologist who founded the school of behaviourism – held that some basic emotions such as anger, fear and love were innate, according to Ferguson, (2000). Watson argued that such emotions were reserved for a limited number of stimuli, and that the range of emotions displayed in adults were “learned reactions” within the realm of classical conditioning (Ferguson, 2000, p. 83). According to Weiner, (1992, p. 305), arousal theory, proposed by Schachter and Singer argued that emotions involved cognition about an “arousing” event and the level of subsequent arousal. Weiner, (1992) further stated that Schachter refined the theory to state that emotional experience followed a sequence of events. Firstly, arousal occurred in the form of a bodily reaction, leading to awareness in an individual of their response. This led to attempts to explain the reaction with an external stimuli being determined and an internal reaction subsequently labelled. It was the resultant labelling that determined the emotional experience for an individual, according to Weiner, (1992). Individuals who were

attuned to “visceral (gut) sensations” and to their arousal levels tended to feel emotions more strongly and intensely, in particular, negative emotions (Shiota & Kalat, 2012, p. 19). Shiota and Kalat, (2012, p. 42) further expanded the concept of emotion to include two adaptive functions of emotion; “intrapersonal” and “social”. Intrapersonal refers to “within-person” which have direct benefits to the person who is experiencing the emotion, for example, fear which results in a physiological change in the body, a change in cognitive thinking, an appraisal and a behavioural change. The social function facilitates people to work together, develop relationships that enable survival and facilitates the transmission of genes. According to Caruso, (2008, p. 5) emotions “direct our attention” and act as motivators for us to take action and quickly prepare individuals for “critical interactions with other people”. Adler, cited by Ferguson, (2000, p. 98), argued that emotion motivated individuals to achieve goals and if aspects of emotion were “maladaptive”, that it was the goals, not the emotion that were the problem.

The important role of culture with respect to emotion has been highlighted with emotions being influenced and shaped by “social, cultural and linguistic processes” (Gangopadhyay, 2008, p. 122). Ekman, cited by Elfenbein and Ambady, (2003, p. 161) put forward the neuro-cultural theory of emotion which held that there was a universal “facial affect program” that provided a one-to-one map between the emotion felt and the facial expression shown. This facial affect programme was the same for all people in all cultures in non-social settings. However, in social settings individuals used management techniques called “display rules” which varied across cultures and were linked with norms which serve to “intensify, diminish, neutralise or mask” displays of emotions which otherwise would be expressed automatically (p. 161). The authors held that individuals were better at judging emotions when expressed by their own cultural group rather than those of different cultural groups. While it is generally accepted that the communication of emotions has a “strong, universal component”, Elfenbein and Ambady, (2003, p. 160) argued that there were subtle differences across cultures which often cause challenges in terms of communication and mis interpretation of messages. In addition, the “emotional context” expanded on this idea of culture to include upbringing, beliefs, past experiences, cultural norms and socialisation, all elements in an “emotional system” which combine to influence individuals in terms of emotional expression (Weisinger, 1998, p. 29). All of the aforementioned have implications for the workplace as workplace organisations are now sites of diversity and change. For example, it may impact on teamwork and communication, therefore, would require some degree of understanding of cultural differences among employees, in particular, with respect to the management and expression of emotions across cultures. These are important considerations in preparing graduates for the transition from higher education to the workplace and will be discussed in more detail later in the review. The brain has been implicated with respect to perceiving, expressing and managing emotion, according to Goleman, (1995) and its role in relation to emotion will be examined in more detail next.

2.1.3 Emotion and the Brain

The brainstem was the first part of the brain to develop and is the most basic part of the brain. It regulates life functions such as breathing and controls reactions and movements (Goleman, 1995). Over time, the emotional centres of the brain evolved and top layers known as the neo-cortex or thinking areas of the brain were identified. The neo-cortex was implicated in the depth and complexity of emotional life, for example, our ability to have feelings about our feelings. The olfactory lobe was the first site of emotion in the brain, with the sense of smell assisting survival in terms of categorising items, for example, into those that were poisonous or edible (Goleman, 1995). The development of the limbic system expanded the emotional capability of the brain and once refined, two important functions of the brain emerged, learning and memory. This was by way of signals entering the brain at the base close to the spinal cord and travelling to the frontal lobes where signals were converted into rational, logical thought patterns. However, firstly these signals travelled through the limbic system, the site associated with emotions, therefore, individuals experienced things emotionally before rational thinking occurred (Bradberry & Greaves, 2009). LeDoux cited by Goleman, (1995), conducted detailed research on the circuitry of the brain and findings placed the amygdala at the centre of the emotional brain with other areas of the limbic structure in different roles. It was held that the amygdala was implicated in all emotional matters and, when severed, resulted in an inability to understand the emotional significance of events. In the 1970s the condition alexithymia became an area of study and was described as an inability to “recognize, understand and describe emotions” caused by a “disconnection between the limbic system and the neo-cortex, particularly its verbal centers” (Bar-On, 2006, p. 14). Alexithymics are lacking in self-awareness and often attribute distress to medical problems when, in fact, the root of such distress is emotional pain, known as “somaticizing”, i.e., mistaking emotional pain as physical (Goleman, 1995, p. 51).

When specifically focusing on EI, Goleman, (1995) argued that the interplay between the amygdala and the neo-cortex were at its core. In scientific research on the brain utilising functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) conducted by Lieberman et al., (2007), results found that affect labelling, i.e., putting feelings into words was of significant benefit as it produced a reduced response in the amygdala and other areas of the limbic system to emotional images leading to more positive emotional responses. According to Robson, (2011) the structure of the brain is greatly influenced by genetic factors, environmental influences, social relationships, diet and nutrition. Goleman, (2013) also highlighted the impact of neuroplasticity in terms of structural changes in the brain throughout the lifespan. Neuroplasticity led to changes in the brain in response to an individual’s (i) experiences, (ii) actions, (iii) relationships and, (iv) specific training. This was significant as it suggested that the brain had the capacity to change and grow throughout the lifespan and that emotional reasoning can also develop and grow throughout the lifespan. It also showed that with training, the structures within the brain can also change and grow which was relevant to this study as a specific EI coaching intervention was implemented.

In leadership studies, Goleman and Boyatzis, (2008) found that effective leadership was linked to social circuits in the brain. This was as a result of the identification of “mirror neurons” in the brain which “mimic” what other people do (p. 3). This was discovered (accidentally) when scientists monitored a particular cell in a monkey’s brain which only “fired” when the monkey raised its arm (p. 3). On one occasion, a laboratory assistant put an ice cream to his mouth which triggered a reaction in the monkey’s cell. This was significant because it demonstrated that when individuals detect emotions in another person through noticing their actions, the mirror neurons reproduce those particular emotions and the neurons create a “sense of shared experience” (p. 3). This is particularly significant in terms of EI in the workplace. For example, when applied to organisational settings, leaders must understand that their emotions and actions may result in mirroring by their subordinates. Therefore, while leaders need to be demanding, it would be important that such demands are executed in a way that instils positivity and good mood in teams (Goleman & Boyatzis, 2008).

The role of the brain has been important in expanding knowledge on emotion and its implications in day to day life. This review will now turn to examine intelligence and then specifically examine the construct of EI.

2.1.4 Intelligence

At the end of the 19th century, individual differences in intelligence emerged with tests of sensory functioning being developed by Galton in the UK, and cited by Brody, (1992), which Galton argued were linked with intellectual ability. In France, Binet and Henri, cited by Brody, (1992, p. 1) held that intelligence could not be measured by simple laboratory tests but by more complex tests of functions such as “imagination, aesthetic sensibility, memory and comprehension”. According to Brody, (1992, p. 5) Spearman’s Theory of Intelligence 1904 argued that all mental performance intelligence was a “construct” and a “hypothetical entity” and recognised the relationship between intelligence and performance in simple sensory discrimination tasks. Spearman, according to Brody, (1992) measured the ability to discriminate different visual, auditory and tactile stimuli and then compared them to performance in exams in different subjects, together with ratings of intellectual capacity for schoolchildren and adult samples. Findings demonstrated a positive correlation between measures of sensory functioning and measures of intelligence across unrelated school subjects. Spearman held that these correlations reflected the influence of an underlying general mental ability factor, labelled g, which impacted on performance on a range of mental tests. In addition, Spearman identified a second factor, specific (s) intelligence which referred to specific intellectual abilities on particular tasks. Brody, (1992) stated that some theorists in the field argued with this finding and held that intelligence tests should be robust in measures that have high generalised (g) to specific (s) ratios. In 1912, Stern created the term IQ which was calculated by dividing a person’s mental age by their chronological age and multiplying this ratio by 100. In the 1940s, Cattell expanded on Spearman’s Theory and suggested that generalised (g) ability could be divided into two abilities, fluid and crystallised (Brody, 1992). Fluid intelligence referred to the capacity to think logically and solve problems in novel situations while crystallised intelligence was the ability to use skills, knowledge and experience accessed through long-term memory.

In the 1920s, Thorndike developed a test of intelligence known as Completion, Arithmetic, Vocabulary Directions (CAVD) and the logic in designing this test was to be the basis for modern intelligence tests (Plucker & Epsing, 2014). Thorndike classified intellectual functioning into three broad categories; abstract intelligence, mechanical intelligence and social intelligence that marked a move away from intelligence purely focused on IQ. According to Oommen, (2014), IQ tests failed to account for other areas associated with intelligence, for example, creativity and EI. In the 1940s, Wechsler, cited by Plucker and Epsing, (2014) expanded the construct of intelligence further and argued that it was a global construct involving a diverse range of skills which could be measured and considered in terms of an individual’s overall personality. Wechsler viewed intelligence as an effect and argued that non-intellective factors, for example, personality, and not purely IQ were significant in the development of intelligence. He defined intelligence as “the aggregate or global capacity of the individual to act purposefully, to think rationally and to deal effectively with his environment” (Wechsler 1944, p. 3).

This was significant as it broadened the notion of intelligence to include interactions with the environment. Such environmental factors influencing intelligence included socio-economic status, nutrition, education, premature birth, pollution, drug and alcohol abuse and mental illness, according to Oommen, (2014).

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children 1949, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 1955 and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), 3rd edition 1997 remain popular tests of intelligence today. In 1950, Piaget argued that every action has an affective aspect and a cognitive aspect; that feelings were motivators to act but

intelligence was implicated in how individuals act, in any given situation (Piaget, 1950). Piaget argued that our “affective” and “cognitive” lives were interlinked but distinct, for example, individuals cannot reason in maths without feeling something and conversely people will not experience an affect or mood without some basic cognitive understanding (p. 6).

In the 1990s, Gardner expanded the theories on intelligence further and argued that the notion of IQ within standard and accepted intelligence tests predicted a person’s ability to manage and complete academic subjects but had little or no influence on determining a person’s success in life (Gardner, 1993). Gardner, cited by Kezar (2001) held that human intelligences were varied and that MI theory addressed three biases: “westist”, “bestist” and “testist” (p. 143). Westist referred to the value placed in Western society on one quality or characteristic over others. Bestist held that the solution to any problem was in one approach. Testist referred to the tendency to focus on human abilities or intelligences that were most easily testable (Kezar, 2001). Gardner presented his theory of multiple intelligences not as “physically verifiable constructs” but as having the potential to be useful “scientific constructs” (p. 70). Gardner, (1993) suggested nine core intelligences; (i) verbal/linguistic, (ii) musical, (iii) logical-mathematical, (iv) visual-spatial, (v) bodily kinaesthetic, (vi) personal: interpersonal, (vii) personal: intrapersonal, (viii) naturalist and (ix) existential (Northern Illinois University Faculty of Instructional Design website n.d.). At the core of each intelligence was a raw “computational capacity”

which was “unique” to that particular intelligence (Gardner, 1993, p. 280). According to Gardner, (1993), multiple intelligence theory was not a “single inherited trait (or set of traits)” which can be determined through an interview or a written test; rather it was linked with highly developed aspects of cognition and aspects of traditional psychology1 (p. 286). This idea of personal intelligence was a major shift in how intelligence was viewed and is most relevant to this research, therefore, it will be the focus of the following section.

Gardner, (1993) argued that personal intelligences were “information processing capacities”, one focusing inward and the other outward and formed a major part of humans as a species (p. 244). Gardner, (1993) argued that knowledge on personal intelligences was critically important, but typically ignored in all studies of cognition and he proffered an important distinction between intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence. In its most basic form, intrapersonal intelligence referred to the ability to distinguish between a range of emotions such as pain and pleasure and involved having “access to one’s own feeling life” (p. 240). In contrast, interpersonal intelligence was described as the ability to focus outward towards other people and weigh up interactions, gauge people’s moods, motivations, intentions and temperament. According to Gardner, (1993), individuals skilled in interpersonal intelligence have the ability to read intentions and moods in others when they are not apparent, and the ability to influence individuals and groups who may be in conflict. Gardner expanded on the concept of the self and proffered that a sense of self emerged from a combination of interpersonal and intrapersonal knowledge, and was greatly

1In traditional psychology, the focus is on the problem with the aim of finding ways to treat the problem using various techniques (Teo, 2006). Past, present and future behaviours of an individual are examined, exploring traumatic event(s) that may have occurred during the individual’s life, and how these event(s) have contributed to the overall functioning of the individual.

influenced by cultural background and experiences. While the concept of EI had not been conceptualised at this stage, Gardner made an important contribution to expanding intelligence as a construct and led the way in terms of the development of EI.

This research is contextualised within a multiple intelligence (MI) theoretical framework. A MI theoretical framework adopts a pragmatic approach to how intelligence is defined and accepts that intelligence is a multi-faceted, complex capacity which includes both cognitive intelligence (IQ) and social and emotional competency (Hoerr, 2000). A MI theoretical framework holds that all people are intelligent, but intelligent in different ways. Every person has potential, however, must be given opportunities to learn and develop. This concurs with research on EI which holds that given the opportunity of EI coaching individuals have the potential to develop and grow in terms of their competency. According to Gardner, (1993) cited by Kezar, (2001, p. 143) the notion of intelligence as multiple resulted in all students experiencing a time in their education where they felt “expert” for a period of time.

This was due to the fact that while most individuals demonstrated intelligence some people had more potential in particular intelligences. When adopting a MI framework in higher education, educators incorporate new approaches to learning such as co operative, collaborative and community service learning as these have been found to work better for some students than conventional methods such as lecturing (Kezar, 2001). Collaborative and co-operative learning involves students working in groups to develop knowledge collectively while community service learning provides opportunities to work in the community to examine particular issues already covered in class. Such approaches can result in the development of both interpersonal and intrapersonal skills in learners. In an educational context, MI increases opportunities

for students to learn and provides different ways for adults to grow personally and professionally. It results in a curriculum that is designed to match students’ strengths with assessment procedures being modified in terms of what is assessed and how it is assessed. A diverse range of assessment measurements are utilised, including portfolios, exhibitions and presentations. Educational establishments are viewed as sites of connectivity and foster links with external bodies and stakeholders (Hoerr, 2000). Kezar, (2001) contended that many higher education institutions were not conducive to the development of multiple intelligences. For example, many did not facilitate group work, did not provide space for introspection or experiential learning and equipment, such as audio-visual or computers were not available. Within a MI theoretical framework, EI is included under personal intelligences and this will be the focus of the next section.

2.1.5 EI

EI is an “intangible” concept affecting “how we manage behaviour, navigate social complexities and make personal decisions that achieve positive results” (Bradberry & Greaves 2009, p. 17). EI emerged from psychological research in two areas; cognition and affect and from models of intelligence (Brackett, Rivers & Salovey, 2011). Cognition and affect examined how the interaction between cognitive and emotional processes facilitated and enhanced thinking. It was held that work performance, the ability to complete tasks, decision making and thinking were all affected by emotions such as anger, fear, happiness, and by “mood states”, by “preferences” and by “bodily states” (Brackett et al., 2011, p. 89). With respect to models of intelligence, such models evolved from primarily focusing on competency at analytic tasks such as memory, reasoning and abstract thought to a much broader picture of mental abilities, which included creative and practical knowledge, all of

which were acquired through interactions with the environment. According to Mikolajczak, (2009), some theorists argued that EI was a set of abilities which constituted a new form of intelligence while others held that EI was related to the personality dimensions and was a set of “affect-related traits” (p. 25). While it is accepted that all humans experience emotion and have emotional responses and reactions, there are marked differences in how individuals “experience, attend to, identify, understand, regulate and use their emotions and those of others” (Mikolajczak, 2009, p. 25). This has led to the construct of EI being developed to account for this variability.

Keefer, (2015, p. 3) held that an essential aspect of human development was the ability to “identify, express, empathize with, and regulate emotions” which were linked with “successful adaptation, social integration, goal achievement, and overall health and wellbeing”. An early argument held that EI competency was genetically fixed or developed in early childhood, however, other theorists held that EI can be learned, developed and enhanced over a lifetime (Goleman 1998; Van Rooy, Alonso & Viswesvaran, 2005; Derksen, Kramer & Katzko, 2002). In 1995, Goleman argued that in order to maintain healthy EI, individuals must find the balance between the extremes of over-expression which can lead to anxiety, anger and depression and emotional suppression which can cause individuals to be dull and distant, which relates to the condition alexithymia, as previously discussed. In a Time, 1995 article EI re-defined the meaning of being “smart” and was posited to be the best predictor of success in life (Mayer, Salovey and Caruso, 2000a, p. 396). While EI is not a “cure for all human problems” it has been described as a set of abilities that can be applied to improve wellbeing and enhance life and career success (Salovey & Grewal, 2005, p. 285). With the expansion of the term EI, different models of EI have been proposed which will be discussed next.

2.1.6 Models of EI

This section will examine models of EI, including Petrides Trait Theory, the Salovey-Mayer ability model, the Goleman and Boyatzis Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI) and the Bar-On Model of Emotional-Social Intelligence (EI), which was the model used in this study. It will present background theory to each model, together with assessment measures. It will then present a critique of EI.

2.1.6.1 Trait Theory

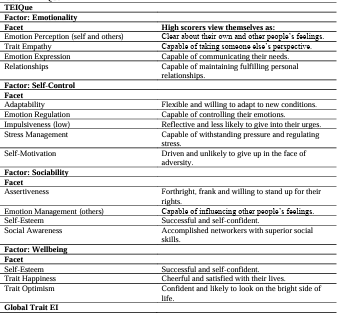

Trait EI or trait emotional self-efficacy is defined as “a constellation of emotional self-perceptions located at the lower levels of personality hierarchies” which recognises the “inherent subjectivity of emotional experience” (Petrides, 2010, p. 137). Many of the genetic factors implicated in the “Big Five personality traits” were implicated in the development of differences in trait EI (p. 137-138). Petrides, (2010) argued that emotional experience was subjective and was part of mainstream theories of differential psychology. According to Petrides, (2010), emotional experience was not constrained by one specific psychological test but was general and allowed for interpretation of data from different questionnaires. In addition, it could be expanded into other models, for example, social intelligence, therefore, it was not restricted to one fixed model. Trait EI is operationalised by the Trait EI Questionnaire (TEIQue) which provides a “gateway” to Trait EI theory (Petrides, 2009, p. 87). The

TEIQue is a self-report measurement which focuses on self-perception and behavioural dispositions which are “compatible” with the subjective nature of emotions (Petrides, 2011). It has four distinct but interrelated dimensions: Emotionality, Self-Control, Sociability and Wellbeing (Petrides, 2009). The test has 153 test items, gives scores on 15 facets, four dimensions and global trait EI (Petrides, 2009). Trait EI scores do not reflect cognitive ability but are scores of “self-perceived abilities” and “behavioural dispositions”, according to Petrides, (2001, p. 663). The TEIQue is a scientific2 measurement tool exclusively based on trait EI theory, however, it is not an alternative to other tests of EI. It affords a “direct route” to the “underlying theory of trait EI”, provides a detailed and comprehensive “average of EI sampling domain” and has increased “predictive validity” (p. 663). See Table 1 for a full breakdown of the TEIQue.

Table 1: TEIQue

Petrides, 2009 in Parker et al.)

2 By being scientific the TEIQue meets criteria in terms of reliability, validity and normative testing.

2.1.6.2 Salovey-Mayer Ability Model

Ability EI is defined as “the ability to perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth” (Mayer & Salovey, 1997, p. 5). Ability models hold that EI is an intelligence similar to any other intelligence and meets three empirical criteria; (i) mental problems have right and wrong answers, (ii) the model measures skills that correlate with other measures of mental ability and (iii) the absolute ability level increases with age (Mayer et al., 2000b). Ability models focus on emotions and interactions with thought processes. The Salovey-Mayer ability model evaluates EI through performance tests focusing on solving emotional problems that include a set of correct and incorrect responses (Gutiérrez-Cobo, Cabello & Fernández-Berrocal, 2017). This model argues that EI involves mental skill in terms of own and others’ emotions and at the development stage, importance was placed on both research on intelligence and emotion. According to this model, an emotionally intelligent person can “harness” both positive and negative emotions and manage them in a way to achieve goals (Salovey & Grewal, 2005, p. 282).

The Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS) was introduced in 2000 and was revised and developed into the Four Branch Model of EI by Mayer, Salovey and Caruso in 2008 (Fiori et al., 2014). The revised model held that emotional abilities lie across a continuum, some of which are at a lower level in terms of executive basic psychological functions while others are more complex in terms of setting goals and self-management. The four abilities form an “emotional blueprint” which together facilitate a better understanding of emotions and helps individuals deal with important situations (Caruso n.d., para. 6). One key aspect of the Four Branch Model of EI is

that these skills operate within a particular social context and individuals must understand the appropriate norms of behaviour with those with whom they interact (Salovey & Grewal, 2005). The test adopts a hierarchal structure with one global underlying factor, EI, four abilities or branches and is scored using consensus and expert based scoring systems (Fiori et al., 2014). In consensus based scoring systems, higher scores indicate higher overlap between individuals’ answers and a worldwide sample of respondents. In expert scoring, the amount of overlap is calculated between individual’s answers and those given by a group of 21 emotion researchers. Table 2 outlines the Four Branch Model of EI.

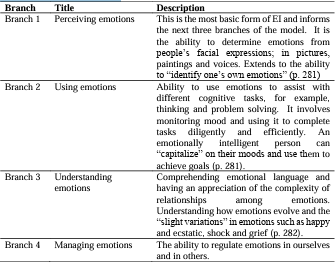

Table 2: Four Branch Model of EI

(Salovey and Grewal 2005)

The model is operationalised by the Mayer, Salovey, Caruso EI Test (MSCEIT), which is detailed next.

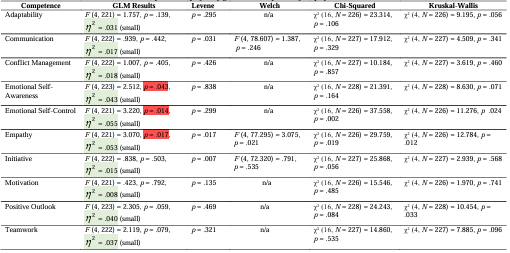

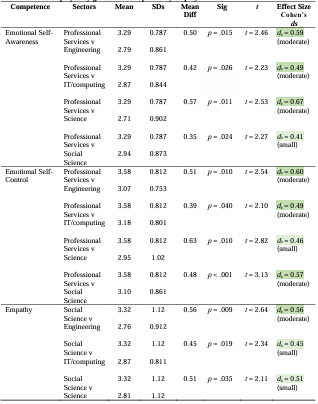

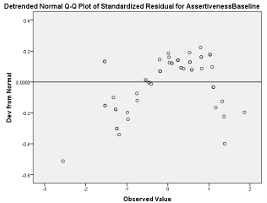

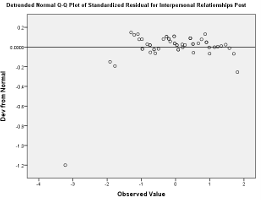

2.1.6.2.1 MSCEIT